I mentioned last letter we'd be delving into a “best-selling” sociology book. What I didn't say was that it’d be the best selling sociology book of all time (I’ll give you a moment to collect yourself).

Is that saying much? Considering the decades since any book in that discipline sold more than, say, 2 copies, yes it is. Launched at dawn of the golden age of sociology in the third quarter of the 20th century, the book harkens from the time of The Organization Man, White Collar and The Authoritarian Personality, before the field fragmented and became enamored of dead ends. It may ring of bell; it’s the beautifully titled The Lonely Crowd by David Reisman.

A former lawyer (who dabbled his way into a supreme court clerkship) with no formal training in sociology who nonetheless became a noted sociology professor at the University of Chicago, his book on the changing character of Americans over its history (to 1950) became a surprise best seller and the subject of popular party chit chat.

The book sold - get this - 1.4 million copies. The publisher expected it to sell a few thousand. Forget sociology - what’s the last original academic book in any discipline that sold anything approaching that?

But the books popularity became both a blessing and a curse. His ideas got caricaturized in popular culture, and broad swaths of folks in academia began looking at him suspiciously. Indeed, he is rarely even mentioned today, or his work seriously engaged with. But historian Rupert Wilkerson provides a corrective to the record on his importance:

[The Lonely Crowd] heralded later findings to a degree that is seldom appreciated. Narcissism and “diffuse anxiety”; the shifting of authority from “dos and don’ts’ to manipulation and enticement; the flooding of attitudes by media messages; the channelling of achievement drives into competition for the approval of others; and the splintering of society into myriad interest groups—all these tendencies of modern American life that so worried commentators [in the following decades] were spotted by Riesman et al. (and well before television had become an everyday staple).

So he “heralded later findings”. Who cares? Would it not be wiser for us practical folk to focus on those “later findings” and throw this book aside as a perhaps interesting but obsolete historical curiosity?

First, the work transcends mere sociology. It’s categorized as a work of “rich description” sociology but in his capable hands it enters into the sphere of sociology as literature.

He had an immense, omnivorous curiosity, a capacious temperament that made him open to a broad spectrum of cultural experiences. He drew on his observations of a wide range of material-children's books, movies, novels, interviews, and social science data. He offered a book that readers read in myriad ways-as an invitation to understand their own lives, as a subject of dinner party conversations , and as a contribution to scholarly cultural criticism. Supple, nuanced, complicated, playful, and lucid, his mind sought imaginative connections between disparate phenomena. The book's style was accessible, its logic complex and even enigmatic. As his friend Eric Larrabee noted, The Lonely Crowd was "[a] witty, garrulous, shrewd, wandering, and intermittently brilliant set of notes that read as though brutal blue-penciling might someday make a book of them." Suggestive and tentative, the book was marked by Riesman's tendency to see issues from multiple perspectives.

It’s a wonderful work of the sociological imagination, inviting questions on the link between history, social structure and who we are and how we choose to live our lives. In contrast to European intellectuals tendency to make messianic broadsides and blanket declarations, Riesman is ever attentive to detail and nuance. It was in many ways a marriage of European social criticism with American social science, in the style of the literary greats.

Still, it’s a 71 year old book which, however literary, still puts forth an explanatory social science framework. One which surely must be - in practical terms - near useless in light of the exponential growth in data in the near century since. Surely we now have advanced theories which better account for the whole of this newer research?

The answer? Not really.

Sociologist Monica Prasad expounded on this just a few months ago:

A central observation, from rationalist practitioners themselves, is that we do not actually see progress in understanding over a century of rationalist social science. Instead, sociological insights, descriptions, and theories come and go as fads. Many different causes for this state of affairs have been suggested. House (2019) worries about “centrifugal forces toward intellectual disunity and diffusion . . . [that prevent sociologists from] making the progress they could and should regarding scientific and scholarly development and contributions to society and public policy”. Besbris and Khan (2017) think that the prevailing demand to develop new theory with every new article “creates cloudiness instead of clarity. We stake the position that a theoretically rich landscape, where theories are plentiful, is one wherein ideas are vacuous”. Another concern is that many scholars spend their time redescribing social phenomena through one or other theoretical lens with no clear reason for selection and no attempt at an overarching synthesis. As Duncan Watts (2017) notes, contradictory findings can thus coexist for decades in the scholarship without anyone noticing or trying to resolve the contradictions, what he calls the “incoherency problem.” Rationalist sociologists find ever more colorful metaphors for this state of affairs, from Besbris and Khan’s (2017) “wheel of fire” to Gerald Davis’s (2015) mystery house with “a number of architectural details that serve no purpose: doorways that open onto walls, labyrinthine hallways that lead nowhere, and stairways that rise only to a ceiling”.

Obviously this is an absurdly complicated subject, at the heart of which lies the tension between individuals and abstractions. But the lack of progress in the field is incontrovertible. It’s the same problem that is plaguing neuropsychology, but at an ever more epic scale: mountains of data, and zero agreement on how to meaningfully parse it and thus move forward.

A “post-critical” future in understanding society means, to my mind, re-engaging with our traditions of thought and tweaking them (if possible) in light of newer research rather than mindlessly throwing out sexy new theories that have only the benefit of bearing one’s name. This theory is sexy enough, lets see if we can shine it up and render it useful.

———-

But what tradition of thought did Lonely Crowd develop out of? Explicitly, it was a response to Tocqueville’s “Democracy in America” (1835) in which Americans were illustrated as being shaped by their daily struggle to conquer nature - where self-reliance and a certain hardness were the norm.

But conditions had obviously changed since and so, according to Riesman, had people. Influenced by a variety of thinkers ranging from Veblan to Adorno, he was particularly drawn (in forming his response) to refine and build on the critical theory work of Erich Fromm.

He was an heir to Fromm’s discourse - started in his most famous work Escape from Freedom - on the downsides of the new freedoms brought on by collapse of the medieval system. Suddenly bereft of embeddedness in communal life and tradition, the individual, Fromm posited;

is overwhelmed with a sense of his individual nothingness and helplessness. Paradise is lost for good, the individual stands alone and faces the world—a stranger thrown into a limitless and threatening world. The new freedom is bound to create a deep feeling of insecurity, powerlessness, doubt, aloneness, and anxiety. These feelings must be alleviated if the individual is to function successfully.

Making matters worse, capitalism instills a new ethos and value system:

The modern market is no longer a meeting place but a mechanism characterized by abstract and impersonal demand. One produces for this market, not for a known circle of customers; its verdict is based on laws of supply and demand; and it determines whether the commodity can be sold and at what price. No matter what the use value of a pair of shoes may be, for instance, if the supply is greater than the demand, some shoes will be sentenced to economic death; they might as well not have been produced at all. The market day is the “day of judgement” as far as the exchange value of the commodities is concerned. [this and the ensuing quotes from Man for Himself]

This way of thinking is then generalized as regards individuals, both others and crucially oneself. It introduces the “experience of oneself as a commodity and of one’s value as exchange value”, and that in turn “becoming salable” became a central concern, at first mostly among upper middle class professionals, but then gradually expanding as this “marketing orientation” began being spread by mass media. “Instead of identifying with great poets and writers, or saints, modern people are connected to ‘great people’ by movie stars, sports heroes, or, more recently, T.V. personalities and rock musicians.”

In other words, the worth of the individual began to be determined by factors he had no control over. Therefore:

one’s self esteem is bound to be shaky and in constant need of confirmation by others. Hence one is driven to strive relentlessly for success, and any setback is a severe threat to one’s self-esteem; helplessness, insecurity, and inferiority feelings are the result. If the vicissitudes of the market are the judges of one’s values, the sense of dignity and pride is destroyed.

Modern identity is as shaky as modern self-esteem for “it is constituted by the sum total of roles one can play.” Since man cannot live doubting his identity, he must, Fromm argues “find the conviction of identity not in reference to himself and his powers but in the opinion of others about him.” For individuals shaped by the marketing orientation,

prestige, status, success, the fact that he is known to others as being a certain person are a substitute for the genuine feeling of identity. This situation makes him utterly dependent on the way that others look at him and forces him to keep up the role in which he once had become successful. If I and my powers are separated from each other then, indeed, is my self constituted by the price I fetch.

This leads individuals to be much more flexible than in previous times, but also more vulnerable to being inordinately affected by whatever their overly developed social “radar”, as Riesman was to later put it, picks up.

———

But before venturing into the book in question, I want to briefly get a better feel of the man. One of the problems with writing about ideas is that it often can become a bloodless affair. But I want his personality and person-hood to shine through, if only for a moment.

One gets a some sense of him in the following early passage. As a law student at the university of buffalo, Riesman wrote:

I spent the summer of 1931 in Russia with a small group of American students. We saw many Russian youths, and in a sense were envious. For they seemed to have no troubles such as confronted us: what to do for a living, what to do for a career.

They taunted me, as capitalist apologist, asking how anyone could be happy in a competitive society, serving himself at the presumed expense of others, serving no greater cause. It was hard to answer them. It was tempting instead to throw oneself, as one of my companions did, into the external, picturesque activity of building the Soviet--building tractors, bridges, railroads. It was easy. After all, we Americans had done just that in the previous one hundred years.Our problems were tougher, for the building that remained for us to do was subtle and complex--the building of a good society...

10 years later, at the age of 27 as a professor of law at the University of Buffalo, he was to have another personal encounter with the ideology. His mother, undergoing analysis with Karen Horney, recommended to David that he see Horney’s colleague - one Erich Fromm:

Riesman agreed to undergo psychoanalysis with Fromm to please his mother... Horney and Fromm had been collaborators during the 1930s in the development of what has been called neo-Freudianism. When Horney recommended Erich Fromm to Eleanor Riesman, David would fly or take the train on alternative weekends for two hour sessions with Fromm in Manhattan. The formal analysis was unconventional, often resembling a teacher/student rather than a psychoanalyst/patient relationship. The analysis continued for some years, however, and was the beginning of a longstanding intellectual relationship and friendship [that continued until Fromm’s death in 1980]. Fromm furthered Riesman’s training in the European intellectual tradition that Riesman had first been introduced to by Carl Joachim Friedrich of the Harvard Government Department. Fromm, according to Riesman, “greatly assisted me in gaining confidence as well as enlarging the scope of my interests in the social sciences”.

The Lonely Crowd was part of an ongoing dialogue, in which agreement and difference both make their mark.

Interesting, Riesman did not share Fromm’s trenchant opposition to capitalism. In fact, he was partially wary of going into analysis with him because he was concerned about attempts to influence him in that direction.

But that ended up not being an issue, and they shared much more in common than they differed. An example: in one of Riesman’s more notable early essays, "A Philosophy for 'Minority' Living," he - in a sentiment reminiscent of Fromm - examines the "nerve of failure," defined as "the courage to face aloneness and the possibility of defeat in one's personal life or one's work without being morally destroyed. It is, in a larger sense, simply the nerve to be oneself when that self is not approved by the dominant ethic of the society."

Both these themes reemerge and then some in his most famous work.

Riesman started the research that led to both The Lonely Crowd (1950) and Faces in the Crowd (1952) with Nathan Glazer at Yale in 1948. They did not have a clear agenda at the time, but undertook interviews in “an exploratory fashion” for a research project supported by the Yale University Committee on National Policy and the Carnegie Corporation. Riesman put together what he calls “a grab bag of questions,” some from The Authoritarian Personality study, from National Opinion Research Center and research produced by C. Wright Mills for his White Collar (1951). As Riesman puts it, they had originally “mulled over these interviews in terms of political orientation” and “the concepts of social character set forth in The Lonely Crowd were developed almost accidentally in working with these vignettes of a few individuals” [Neil McLaughlin]

So they came across this theme of “social character” which is the “more or less permanent socially and historically conditioned organization of an individual’s drives and satisfactions—the kind of ‘set’ with which he approaches the world and people”. This is similar to Bourdieu’s Habitus (one’s “feel for the game” and the things one “just knows”), and also Bateson’s combination of epistemology and ontology.

So what, in as unbutchered a manner as I can find, is the message of Lonely Crowd?

Here’s Robert Fulford with a succinct summary:

In every age, certain personality types rise to prominence. Wars call forth warriors, and an era of expansion calls forth adventurers. What sort of people flourish in the age of organization? Answering that question, Riesman sorted character types into three defined but overlapping categories.

Those categories are the tradition-directed, the inner directed and the outer directed. Which of course are not “pure” categories, everyone is some mix but they are more apparent in certain ages and settings.

Tradition-direction folks tend to live in (ancient) communities where the idea of the differentiated self was uncommon to unknown. The whole idea of “finding” and “being” oneself would have been largely incomprehensible to such people. You were the son or daughter of so-and-so, you did whatever it was that they did (in work particularly), you had kids who did the same, and that was that.

This type of individual “having little reason to suspect that the future will be much different from the present, is guided principally by the way things have practically speaking always been done, and views his parents—along with the Church, the village blacksmith or wheelwright, etc.—more as conduits of this traditional way than as self-sustaining centers of authority.”

Riesman gives the example, “For centuries the peasant farmers of Lebanon suffered from invasions by Arab horsemen. After each invasion the peasants began all over again to cultivate the soil, though they might do so only to pay tribute to the next marauder. The process went on until eventually the fertile valleys became virtual deserts, in which neither peasants nor nomads could hope for much. The peasants obviously never dreamed they could become horsemen; the marauders obviously never dreamed that they too might become cultivators of the soil. This epic has the quality not of human history but of animal life. The herbivores are unable to stop eating grass though they eat only to be devoured by the carnivores. And the carnivores cannot eat grass when they have thinned out the herbivores. In these societies dependent on tradition-direction there is scarcely a notion that one might change character or role.”

Inner directed folks in contrast tend to live in societies where questions about the self become both askable and pertinent, and their answer to that question is is find and internalize the authority of a specific source. “The inner-directed type gets his full panoply of values directly and entirely from their “parents and other authorities [chiefly printed texts, from the Bible to classic novels to secular hagiographies of great men]” and, impelled by the infrastructural cravings of an ever-burgeoning and ever-more-widely dispersed population, blinkeredly, and essentially in solitude, applies them for the balance of his life to various concrete political, administrative, technical, theoretical, or artistic tasks—abolishing slavery, building railroads, founding Poughkeepsie or Sheboygan, devising a law or two of thermodynamics, writing The Scarlet Letter or The Portrait of a Lady. The inner-directed type’s psychological mechanism may be likened to a “gyroscope […],” which, “once it is set…keeps [him] ‘on course’ even when tradition, when responded to by his character, no longer dictates his moves,” and his strongest actuating emotion is guilt.” These folks tend to be confident but also rigid.

So even though tradition-directed and inner-directed folks may end up with similar lifestyles, their thinking and motivations are quite different. Tradition is the authority that they conform to, not particular people or institutions (living or dead), as opposed to the inner-directed.

Finally, to the self that Riesman postulated had achieved ascendency: the other-directed.

“The other-directed type finds himself rather empty-handed with no cities to found, railroads to build, etc., and is obliged to turn willy-nilly to other people—of whatever stripe, and wherever they may be found—for ethical guidance, approval, and… the plastic stuff of his individual industry. In an other-directed directed (sic) world, graying parents must manipulatively vie with teenagers or even toddlers for pride of place in their children’s worldview; work becomes more a domain for cultivating a sort of personal fan club (“glad-handing,” Riesman calls it) than for actually getting anything done; and leisure time is devoted largely to one-upping one’s neighbor on “marginally differentiated” niceties of food-preparation, peeping-Tommish or conspiracy-theoretical political gossip (the stock-in-trade of the other-directed “inside-dopester” as against the inner-directed “moralizer”), and the like. As the other-directed person must “be able to receive signals from far and near,” and the sources of these signals “are many, the changes rapid,” his “control equipment, instead of being like a gyroscope, is like a radar”; and one of his “prime psychological lever[s] is anxiety.” (Robertson)

Marked mostly by his sense of direction coming from his contemporaries - either directly or through mass media, the other-directed person “is cosmopolitan. For him the border between the familiar and the strange—a border clearly marked in the societies depending on tradition-direction —has broken down. As the family continuously absorbs the strange and reshapes itself, so the strange becomes familiar. While the inner-directed person could be ‘at home abroad’ by virtue of his relative insensitivity to others, the other-directed person is, in a sense, at home everywhere and nowhere, capable of a rapid if sometimes superficial intimacy with and response to everyone”.

——-

So Reisman divides the world into three loose, overlapping “types” and posits that 2 are dying and the third is ascendant. All three are problematic in different ways, and the ideal is towards developing what he calls autonomy.

Assessing this thesis the light of present data is difficult. But I am less interested in the degree to which this “change in character” was true in 1950 than what has happened in these dimensions in the years since, and what is the case today.

First though, Riesman’s thoughts on what the future would bring and why:

The more advanced the technology, on the whole, the more possible it is for a considerable number of human beings to imagine being somebody else… technology spurs the division of labor, which, in turn, creates the possibility for a greater variety of experience and of social character…

…the improvement in technology permits sufficient leisure to contemplate change—a kind of capital reserve in men's self-adaptation to nature—not on the part of a ruling few but on the part of many…. [and] the combination of technology and leisure helps to acquaint people with other historical solutions—to provide them, that is, not only with more goods and more experiences but also with an increased variety of personal and social models.

Today again, in the countries of incipient population decline, men stand on the threshold of new possibilities of being and becoming—though history provides a less ready, perhaps only a misleading, guide. They no longer need limit their choices by gyroscopic adaptation but can respond to a far wider range of signals than any that could possibly be internalized in childhood.

And there are several indicators that are at least suggestive of growing non-other-directedness. Conformity on the Ash line test decreased between the 1950’s and 1990’s, and first person singular pronouns increased and first person plural ones decreased in American English books between 1960 and 2008 (if you know of any other relevant data-sets please feel free to reply or comment).

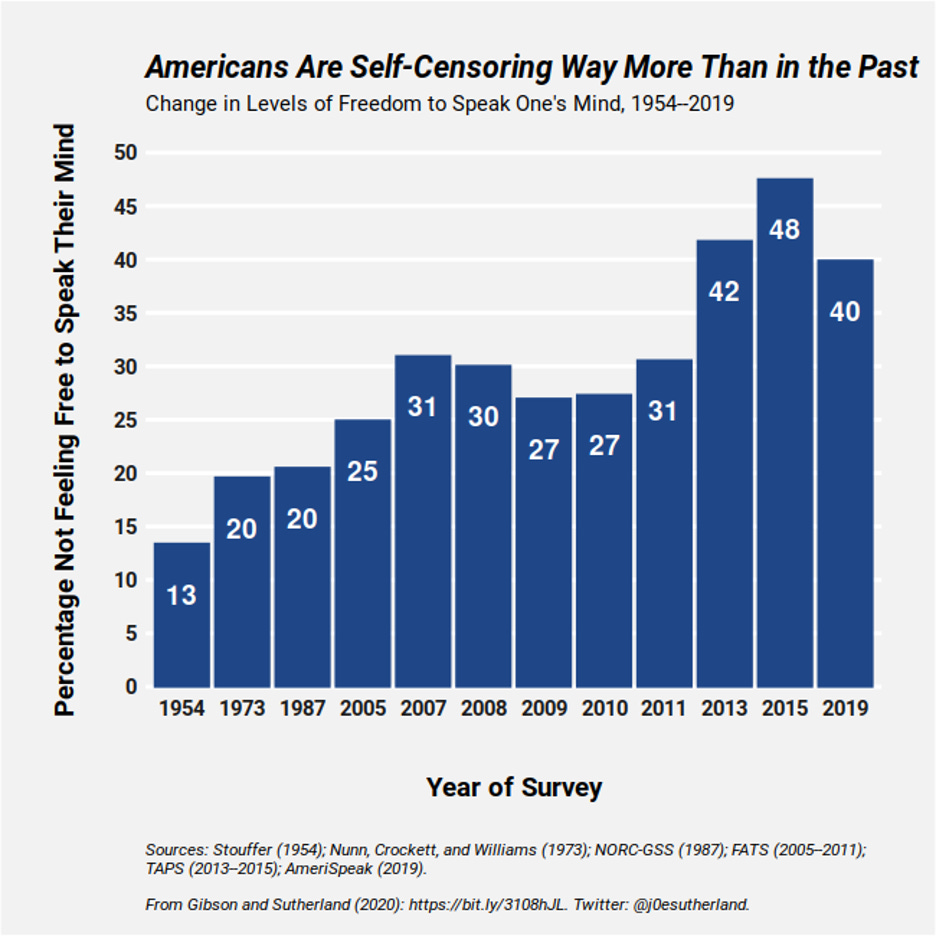

On the other hand, there’s been a dramatic increase in self-censorship between 1954 and 2019 and a steady rise in anxiety from 1938 to 2007.

How to make sense of these seemingly contrasting results?

Riesman suggests an answer:

…heightened self-consciousness, above all else, constitutes the insignia of the autonomous in an era dependent on other-direction. For, as the inner-directed man is more self-conscious than his tradition-directed predecessor and as the other-directed man is more self-conscious still, the autonomous man growing up under conditions that encourage self-consciousness can disentangle himself from the adjusted others only by a further move toward even greater self-consciousness. His autonomy depends not upon the ease with which he may deny or disguise his emotions but, on the contrary, upon the success of his effort to recognize and respect his own feelings, his own potentialities, his own limitations. This is not a quantitative matter, but in part an awareness of the problem of self-consciousness itself, an achievement of a higher order of abstraction.

The decrease in conformity to the Ash line test suggests such an increase in self-consciousness, at least in terms of own present moment experience of the world, as does the increase in first person singular pronouns. The increase in self-censorship to my mind actually confirms this: individuals, being more aware of their own position also become more aware of difference. You can’t self-censor if you don’t know your own thoughts.

But the fear of speaking up in the face of difference, and the capitulation to that fear, along perhaps with the increase in anxiety suggests another ingredient is missing. It suggests that the authority of others has been reduced only in situations in which autonomous action is perceived as no threat to others. That we are as aware if not more so of others opinions - the “social radar” is ever alive and powerful - but it is now contrasted with an ever increasing degree of self-consciousness.

And that contrast may play a role in that increase in anxiety. Faced with difference, what do we do?

To be fair to the complexity of Riesman’s thought - autonomy does not automatically mean not conforming. It means the choice is available to the individual whether or not they wish to do so. The “directed” and the anomic in comparison have no choice.

So the degree to which the self-censored are doing so of their own volition is key. The data is not encouraging - it suggests that fear is the primary driver of self-censorship as this fear has grown in sync with the rise of the former.

So present moment self-consciousness is not enough to attain autonomy, at least in matters of any importance. Something else is needed. But what?

When someone fails to become autonomous, we can very often see what blockages have stood in his way, but when someone succeeds in the same overt setting in which others have failed, I myself have no ready explanation of this, and am sometimes tempted to fall back on constitutional or genetic factors—what people of an earlier era called the divine spark. Certainly, if one observes week-old infants in a hospital creche, one is struck with the varieties in responsiveness and aliveness before there has been much chance for culture to take hold. But, since this is a book about culture and character. I must leave such speculations to others.

Obviously constitution plays a role, but looking at this broader trend other variables are indicated.

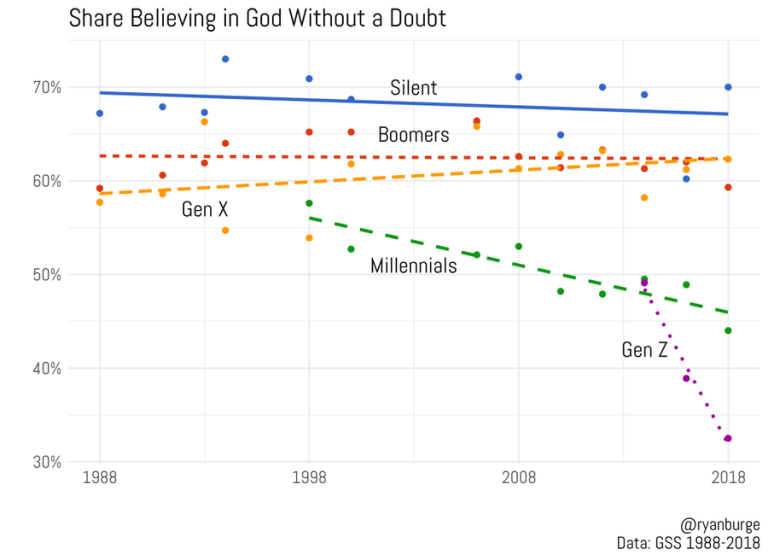

What I want to suggest is that we’ve over-corrected. We’ve killed off tradition, we’ve murdered our childhood idols and authority figures, and God himself as well.

Not only do they not have explicit authority anymore, they barely have a conscious influence. All of our decisions turn into (relatively) dichotomous ones between others and ourselves and this “far wider range of signals” has - consciously at least - been reduced to just us and our contemporaries. We’ve constricted, and not expanded.

Not that any of these murdered figures have gone anywhere. They haunt us still, but now unawares. Gifted with the “present” and “each other” to the exclusion of all else, our reward is ever increasing rates of anxiety and distress.

Going back to Riesman, we’ve compensated for an increase in present moment self-consciousness and of our experience of the other by decreasing our consciousness of tradition and inner experience. The pendulum has swung too far to the left.

——-

The sense of being a link between the past and future, between who came before us and who will come after is a large part of what gives existence weight and meaning. But our often tenuous grasp of what preceded us and the myth of progress often robs this knowledge of much of its power. Benighted and faithless, trapped in a decontextualized universe, the great figures of the past are often turned into caricatures, reduced to an idea, a quote, an anecdote.

Banalized, their existence as bodies is eradicated from discourse - pre-empting attempts to relate to them as such.

Is it any wonder that the present age is put on a pedestal? That our peers often become our bondage-holders?

A promising counterbalance to these trends is to develop alternative ways of being that increase and diversify the “crowd within” - and drive an ongoing inner discourse so that this crowd is less lonely and alienated. So that archetypes or perennial roles or “offices” are in communication with the great wisdom traditions, and the important figures from our childhoods, and can provide a conscious contrast to the figures of the present age. That can be summoned in moments of distress and conflict.

It’s to look more often within, and behind, to develop depth and soul and all that old-fashioned banalized goodness.

And we could do worse than to turn to Jung for a starting point in that journey.

P.S. Please pardon the cursory closing; all of these themes will be re-examined in later installments - this letter was meant as an almost whimsical aside that unexpectedly ballooned.